By Mastering The Mix contributor: Nick Messitte.

I’ve seen the best mixes of my generation destroyed by fancy stereo imagers instantiated on every stereo track. I’ve seen them ruined by mid-side EQ, overused delays, and polarity flips that make the listener woozy.

Width is the holy grail, and many budding engineers sacrifice much in searching for it. Here’s the truth: achieving width is exceedingly simple, but it’s never easy; panning, level changes, transient manipulation, equalization, and time-based effects—these are the bread and butter of width.

Master our simplest tools, and you’ll be the master of the stereo image. We’ll show you exactly how in the following tips.

Use clear, delineated panning positions

Width is inherently relational: you need to play one element off another to create a stereo picture.

Let’s use a simple example—a double-tracked guitar part—to show off what we mean. Here we have one guitar playing up the middle, and another doubled hard left.

EXAMPLE 1

Doesn’t sound too wide, does it? But if we move the center guitar part even a little to the right, it feels automatically wider.

EXAMPLE 2

Of course, “panning affects width” isn’t the statement of the century—until you remember how complicated things become when we add multiple instruments in competing frequency ranges: drums, keys, synths, vocals, more guitars, bass, et cetera.

When the mix gets more complex, the pan knob alone will not save us. So, like a contractor, we stack more elements on our solid foundation of panning: frequency, level, and transient impact become determining factors in our panning decisions.

Consider the first example, with one guitar panned hard left, and the other playing up the center: it didn’t sound all that wide.

EXAMPLE 1 AGAIN

However, if we took the center guitar part and raised it up one octave—even with something as simple as a pitch shifter—it does sound a lot wider.

EXAMPLE 3

See, we have created complementary frequency ranges. Because our ear isn’t fighting to locate the same frequency ranges in two places, the ear delineates the panning position better.

So here, we do not need to pan the center instrument over to the right, because it’s already delineated. This allows us to place something entirely different in the right, a complementary instrument.

Nick’s favorite tools for panning: Your DAW’s pan pots; DMG Audio Track Control.

Carefully consider your levels

Level is our next determining influence. Let’s examine our guitars again: we made them feel wide by moving the center part over to the right.

EXAMPLE 2 AGAIN

But what happens if I drop the hard-left guitar 10 decibels?

EXAMPLE 4

Our width is severely curtailed! Not only that, our whole stereo picture has shifted to the right.

So you see, we must seek an appropriate balance in level when width is our goal.

Nick’s favorite tools for level: Your DAW’s fader; your DAW’s gain/trim plug-in.

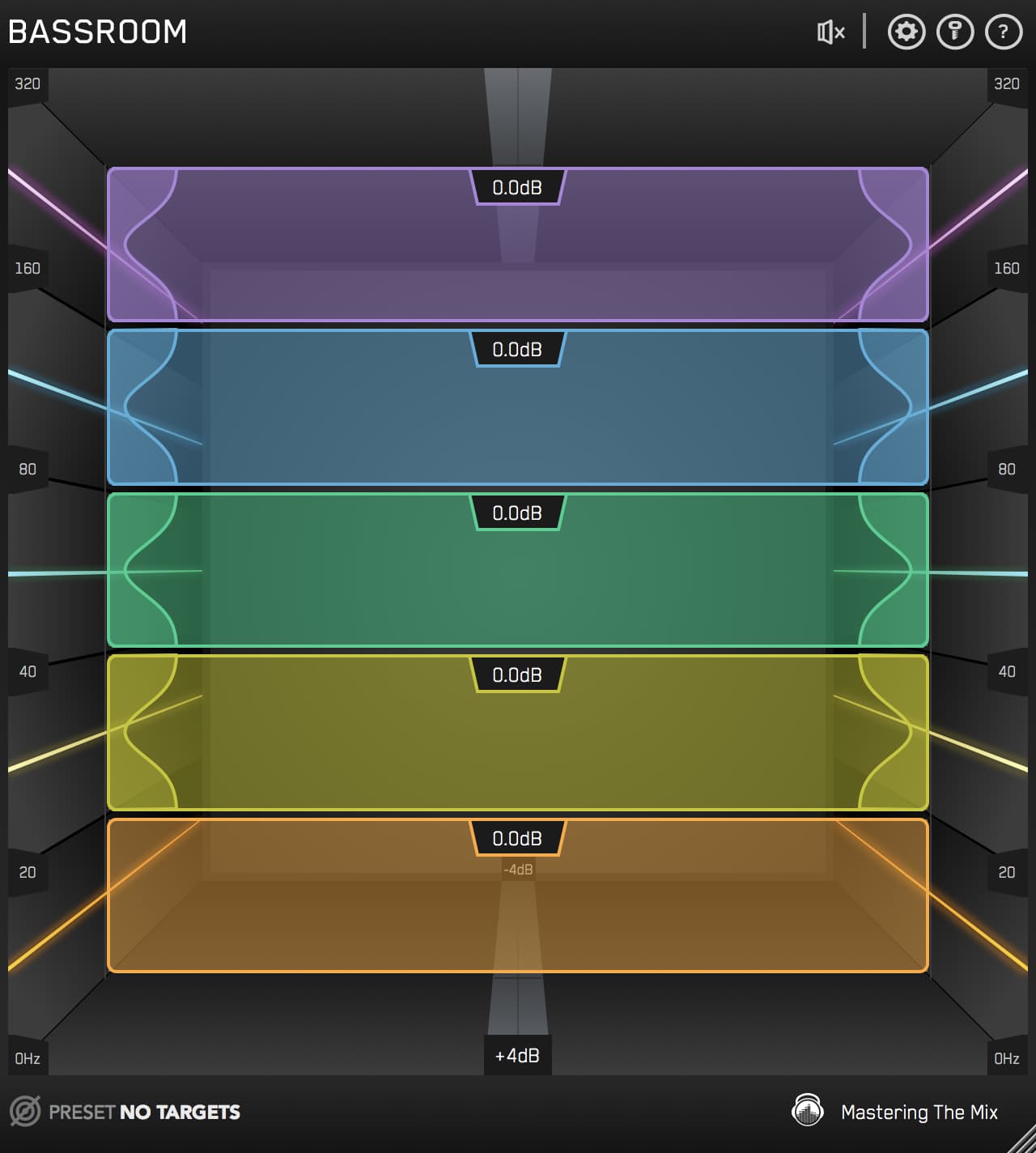

Preserve your transients

Perhaps you’ve over-compressed the stereo bus and noticed it sounded smaller. If so, you already understand what I’m about to say: transient manipulation can severely impact the stereo image.

Transients are what our ears perceive first—and if we smear them, the width will suffer.

Let’s take our two-guitar example and add a third: a lead part that makes achieving a stereo a more complex affair.

EXAMPLE 5

A nice balance. But what happens if we destroy the rhythm guitars with a transient shaper, stamping down the attack and emphasizing the release?

EXAMPLE 6

The lead is present, but the rhythm guitars have lost definition. The result is a reduction in apparent width because our rhythm guitars are now indistinct.

Our ears can’t locate them as well. Their impact has been softened, like a picture with a dirty thumbprint on the corners.

Let’s now do the opposite—let’s use the transient shaper boost to the attack of our rhythm guitars:

EXAMPLE 7

Now we are alerted to each transient as it happens. The transients draw our ears to the corners of the mix, and they don’t interfere with the lead; the result is width on a grander scale.

The takeaway? Compressors, limiters, and transient shapers can restrict feelings of stereo width.

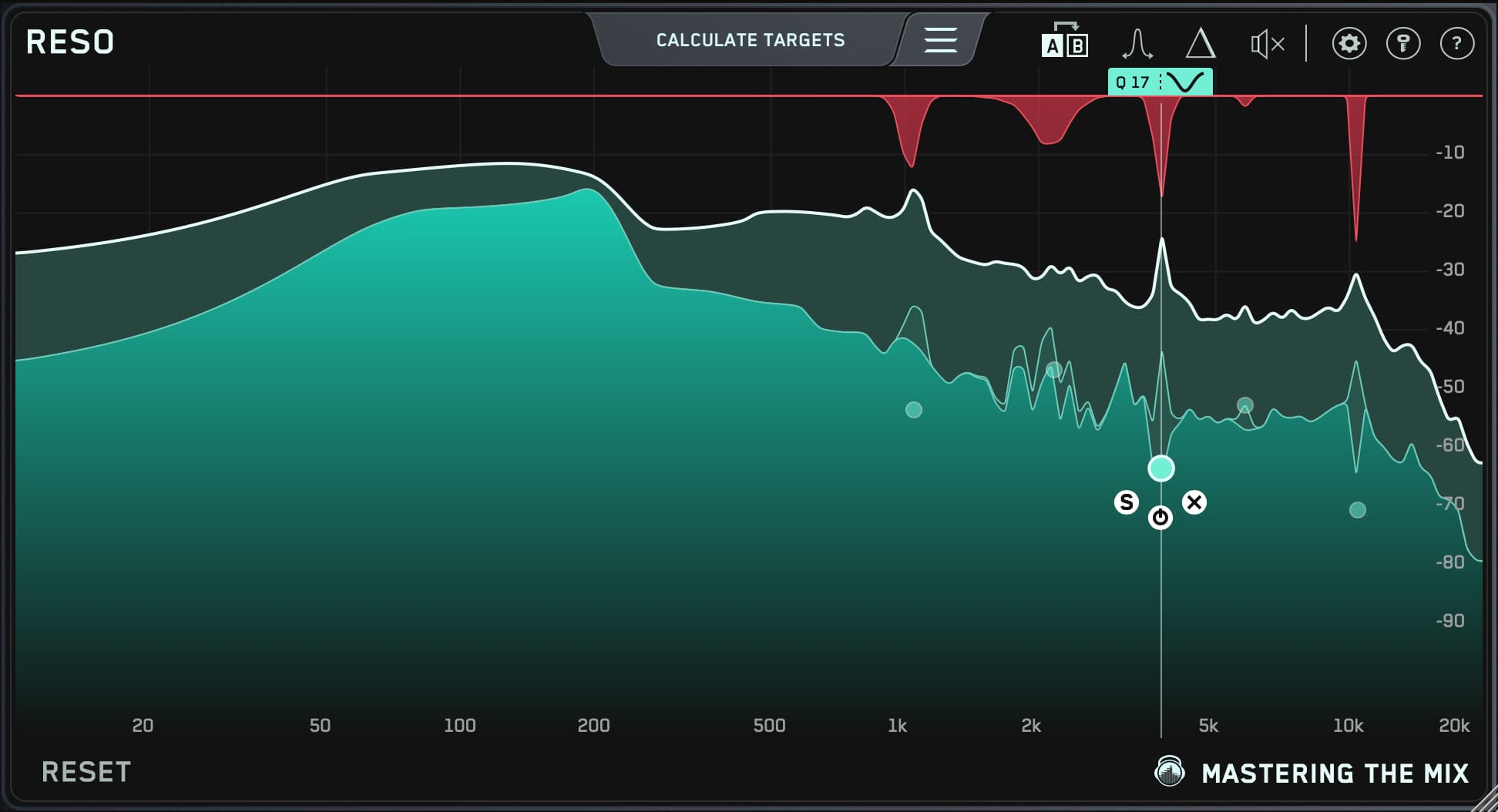

But that’s not all: stereo-width processors can also kill your transient response, albeit in a different manner. Many stereo-width plug-ins pan frequencies in an interesting way.

This is a popular imager fed with a mono signal in Plugin Doctor. The purple line is our left channel, and turquoise is our right.

Notice how each notch in the left is reflected by an equal boost in the right: our mono signal has been sliced and diced into stereo through frequency manipulation.

All well and good for a pad—but if you put this on a snare drum, what’s going to happen to the snap, crack, and pop?

Boosted in the left, cut in the right, the snare drum’s position will be harder to discern. Our ears will have a devil of time pinpointing the snare’s directionality. Such indistinction messes with the stereo picture.

Nick’s favorite tools for preserving transients: Mastering the Mix ANIMATE (all modules), FabFilter Pro-MB (in expansion mode), iZotope Transient Shaper (found in Neutron 3). Soundtheory Gullfoss (the EQ calculations this plug-in performs every millisecond help preserve transients, I find).

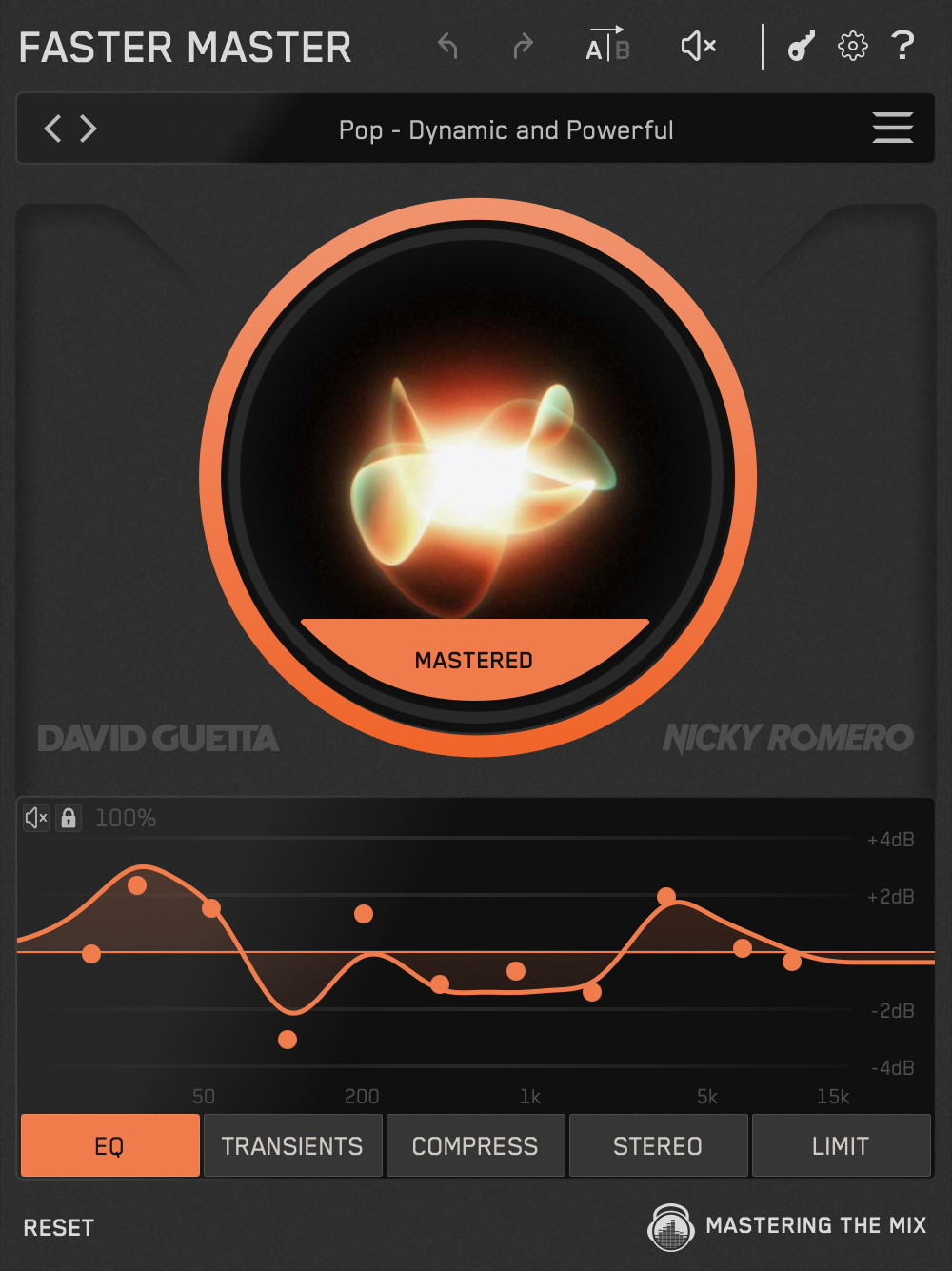

EQ your instruments and FX to bring out the right elements

Let’s take our rhythm guitars and mess with their EQ response. Here’s what I’ve done to the guitar panned hard right:

And here’s the right channel guitar:

It sounds like this:

EXAMPLE 8

Note how our whole picture has been cheated to the right. Also, our right-panned rhythm guitar fights with the lead. Compare this example with the previous one, and you’ll note how muddy and indistinct it sounds by comparison.

Conversely, I can change the EQ scheme to emphasize the pick attack of both guitars. Then, I can select which bits of midrange meat I want to hear in each channel, and suffuse more definition into the picture:

Left

Right

EXAMPLE 9

The takeaway? If EQ causes indistinction, our picture will be out of focus.

This isn’t true for instruments alone. It also applies to effects like reverb and delay, which leak all over the stereo field if left unattended and compete with both necessary transients and vital elements.

Now, if you EQ your effects to stay away from these important corners of the mix, you can preserve your stereo image.

Be sure to EQ a verb away from the vocal’s most prominent frequencies, or away from the kick’s heft, or the snare’s snap. Make certain that a thick delay—such as a tape delay—isn’t competing with a vital instrument, especially if they’re panned to similar locations.

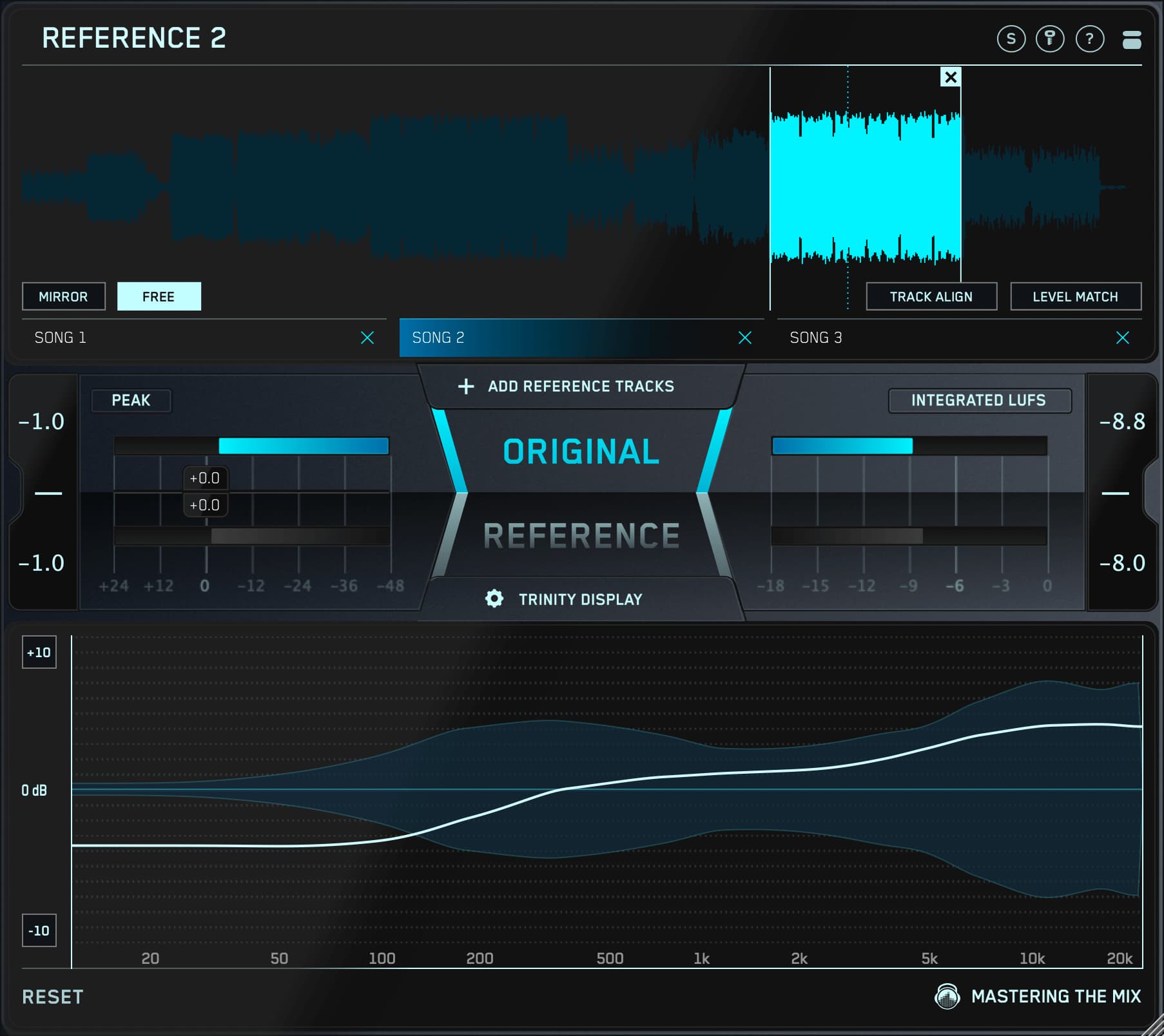

Consider how you’re using Mid-Side EQ

No doubt you’ve been warned not to overdo mid-side EQ. Nevertheless, you should be warned again, and here’s why:

Mid-side is not an accurate term. The more appropriate one is sum/difference: what you call “mid” is your left and right channels summed together—mono. The “side”, technically speaking, is also mono—but it consists of your left channel summed with a phase-inverted right channel.

I’m not going to get into the science of it, for that would bore you to tears. Instead, I’ll highlight the essential problem:

If you have an element panned hard left, a mid-side EQ will always mess with that element, no matter if you choose the mid or side channel.

That’s why an abundance of mid-side EQ can really destroy a loop, a stereo instrument, or a mix: you can create a woozy, unnatural feeling by dissociating one “copy” of an instrument from the other.

Nevertheless, there are some worthy mid-side tricks to try:

If you’re working with a stereo loop during a mix, cut the low end to an appropriate degree. This will help it take up less space in the mix, giving you more room in the corners to place other elements and to create a feeling of width.

If you’re mastering or working on the stereo bus, try the same tip as above, for the same reasons.

If you’re working with a stereo loop or a stereo instrument, try notching some of the midrange out of the center channel. Find where the vocal is prominent and make room for it with a mid-side EQ—or with Leapwing’s CenterOne, which uses an entirely different proprietary process.

Again, don’t go too far, or you might destroy the integrity of the element you’re EQ’ing.

Nick’s favorite tools for M/S EQ: Mastering the Mix LEVELS (for monitoring your sides during the high-pass filtering trick), CraveDSP Crave, FabFilter Pro Q3, Leapwing CenterOne (again, this is not an M/S process, but it achieves the same goal—often in a cleaner way).

Delineate sections of the mix to improve the stereo image

If you start a mix wide and never veer off that course, it will feel narrow by the end of the mix, simply by remaining so static.

Consider that you can’t have a wide chorus without a narrower verse: Width is relational.

Try panning the instruments closer to center in the verse, and going to edges of the mix for the chorus. A sectional change like this can inject a feeling of width.

When going wider in the chorus, you can also use plug-ins that make use of short stereo delays, thereby taking advantage of the Haas effect.

Now, do not overuse this effect! It will ruin your mixes if thrown around willy-nilly. Instead, try employing Haas-style trickery on one element of the mix, preferably on an element of no great rhythmic importance.

Nick’s favorite tools for Haas effects: Mastering the Mix ANIMATE —particularly the Grow module. This unique expander can grab anything within a selectable frequency range, and anything above a selectable threshold. Instead of making the material “louder” it will make it momentarily wider. Use Animate for rhythmically widening pads, and clearing bass out of the kick drum’s path.

Also, your DAW’s stereo delay is good for Haas delays.

Conclusion

We started this article with a heck of an unexciting statement: there are no secret weapons for stereo width; only mastery of the basic tools and techniques will save you.

Hopefully, though, we have done enough to demonstrate why that should be exciting, rather than dismaying; hopefully, our examples have driven the point home, showing you what you can do with the tools you have.

But, if you do crave more tools, make sure they’re the ones that will really animate your mix. Pun intended.