Before its release in 1975, the label executives surrounding Queen suggested that Bohemian Rhapsody was too long (at 5 minutes 55 seconds) and could never be a hit. Even Queen’s musician friends commented that it would struggle to get radio play. Their educated guesses were not unfounded due to the unusual composition featuring no chorus, combining diverse genres, and the dark lyrical content.

Against all the odds, the song was a huge success topping the UK Charts for 9 weeks and then reaching number one again for 5 weeks in 1991 following singer Freddie Mercury’s death. Bohemian Rhapsody has now been streamed more than 1.6 billion times across Spotify and YouTube, making it the most-streamed song from the 20th century. Bohemian Rhapsody is also the title of Freddie Mercury’s biopic which has grossed more than $900 Million at the box office.

- UK Number 1 for 9 weeks in 1975.

- UK Number 1 for 5 weeks in 1991.

- More than 1.6 Billion Streams on Spotify & YouTube.

- Most streamed song from the 20th century.

The song broke sonic barriers. It was an incredibly well crafted and intelligent composition made possible through the band's deep understanding of music theory and harmony. The fusion of an accessible prog-rock sound and story-telling opera has helped it resonate with audiences across generations.

There are many layers of complexity that make Bohemian Rhapsody great, and the genius nuances might only ever be known by Mercury himself. Let’s explore the components of the song to see what can stimulate our creative spirit.

Teasing The Release

Capital Radio DJ Kenny Everett was given a pre-release copy of Bohemian Rhapsody but was given strict instructions not to play it, even though he had predicted it would be a hit. He teased his listeners by playing only parts of the song and would claim it was an accident, telling listeners that “His finger slipped.” The audience went crazy for the song, demanding to hear the full version, and even showing up to the radio station and record stores to try and buy a copy before its release. Everett finally relented to the listener’s requests and played the song 14 times over two days.

Though this wasn’t a planned strategy, it built hype and got people talking about the record. Try a similar strategy for your next release and see if teasing your audience by releasing a section of your track generates buzz.

Stereo Separation

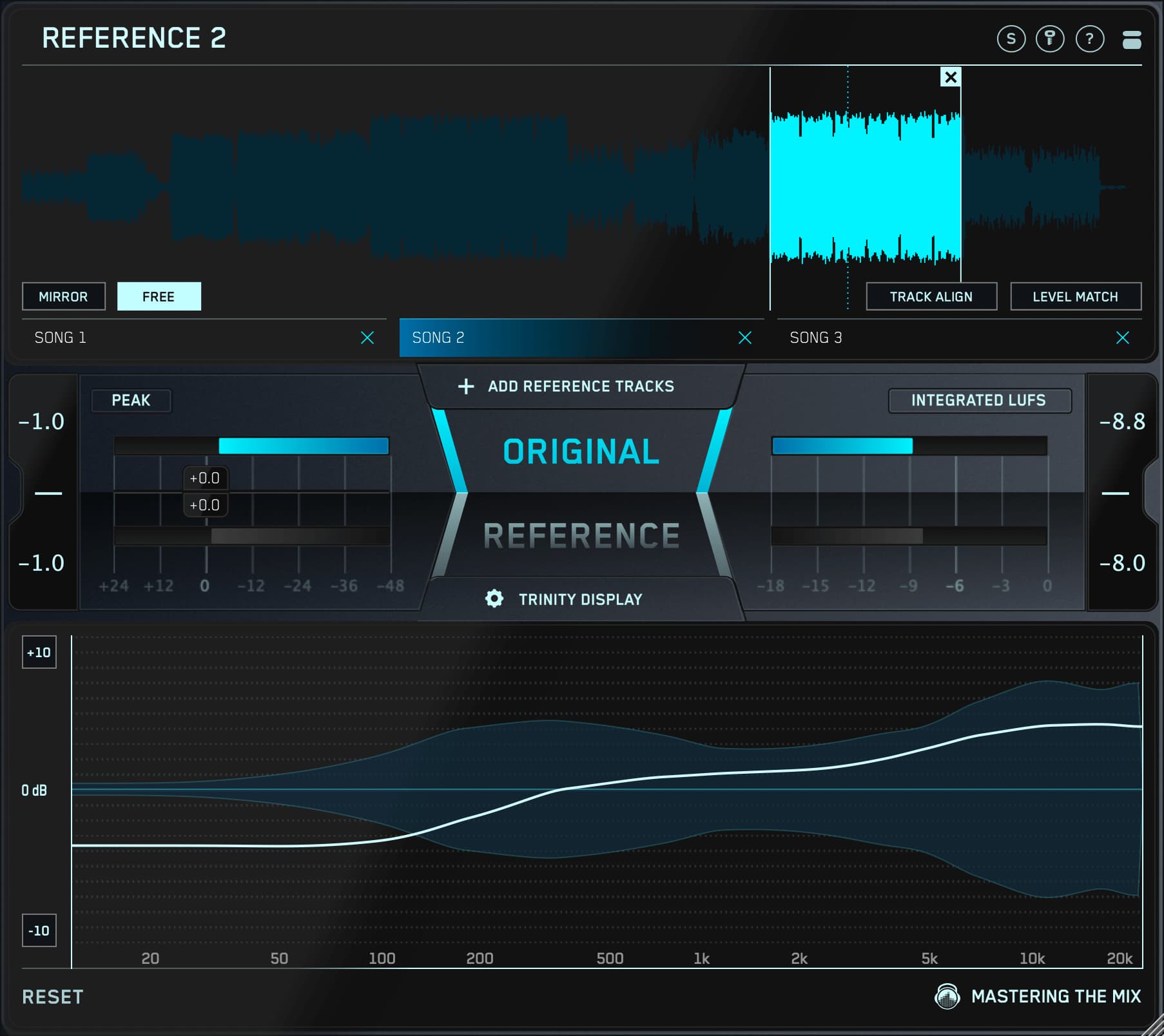

Below we have an infographic showing the frequency and stereo placement of the instruments during the rock section (4:08 to 4:46) in color. Notable elements of the mix from previous sections are also shown in white.

The vocal is double-tracked and panned slightly left and right giving it an interesting sense of space. Mercury was so consistent when duplicating his vocal parts that they would sometime phase; however, his performance here introduces rhythm variations purposefully to get a more rocky feel. They’re still panned fairly central to give space to the guitar.

The guitar gets it’s thick and wide tone from two separate takes being used panned far left and right. The tone of Brian Mays guitar constantly evolves throughout the song. Even during the Rock section the tone of the guitar after the vocals is slightly different from the tone of the guitar before. This was done intentionally to create new textures of sound, but also helps the overlap of guitar parts during overdubbing.

The bass plays a supportive role here and holds the foundation while the vocals and guitar take the spotlight. Its clean tone means it doesn’t add unnecessary distortion to compete with the guitar. It’s also placed centrally in the mix allowing the guitar the freedom to come as low as 100Hz in the side channels.

Structure, Arrangement, and Journey

Bohemian Rhapsody is a six-minute composition, consisting of 6 distinct sections without a chorus: an intro, a ballad segment, a guitar solo an operatic passage, a hard rock part, and a reflective outro coda.

The instrumentation remains consistent with Queens classic line up, Freddie Mercury singing and playing piano, Brian May on guitar and backing vocals, John Deacon on Bass, and Roger Taylor on drums and backing vocals. While the guitar has over-dubs and doubled parts to give the song a thicker sound, it’s the rich vocal harmonies that provide the sense of an epic and grand arrangement.

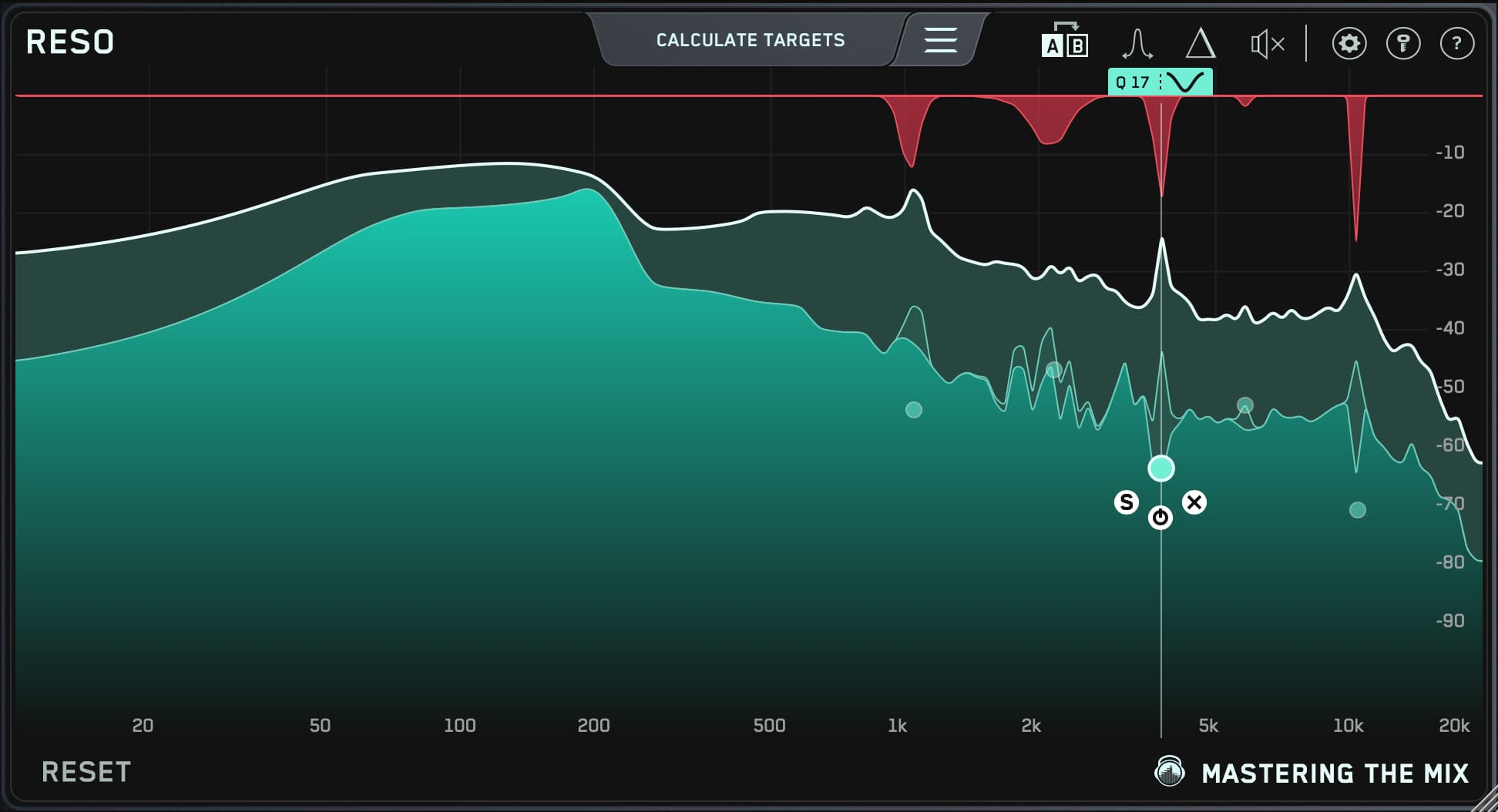

Below we can see where the different instruments enter the mix to create different sonic textures for each passage. Notice the sparse instrumentation of the intro and outro and the dense arrangement during the guitar solo and rock section.

Creating a single cohesive piece of music out of dramatically different melodies and tempos points to influences from the symphonies of Beethoven and the operas of Mozart. Mercury said in an interview in 1985, "It was basically three songs that I wanted to put out and I just put the three together.”

The transitions are masterful and seamless, keeping the flow of the music through intelligent use of dynamic performance. For example, the ballad builds it’s intensity as it gets closer to the guitar solo. The guitar solo stops abruptly to introduce the opera which is in keeping with the dynamic changes of that section. The opera becomes denser as it approaches the rock section, and the tom fill helps connect the two. The rock section gradually winds down as it transitions into the peaceful and sparse outro. Making the transitions flow musically from one section to another helps the sequence and continuity of the song.

Recording Techniques

Bohemian Rhapsody was recorded at Rockfield Studios over three weeks. In 1975 it was considered to be one of the most expensive rock albums ever made costing around £40k (around £330k today adjusted for inflation).

The rich sound of the harmonies was created by Mercury, May, and Taylor, each singing every note in the chord and stacking the performances; there were as many as 180 overdubs. For this to work and stay intelligible the timing of each vocal delivery had to be exact regarding rhythm, pitch, and vocal inflection. As they were working with 24-track analog tape, the three needed to overdub themselves many times and bounce these down to successive sub-mixes.

The instrumental performances were also crucial to the success of the recording. The bass timing is completely locked into the left-hand piano part (as humanly possible) which helps fuse the instruments. The guitar was often double-tracked with the lead melodies played an octave lower to thicken the sound. Again, an identical performance with minor human errors was needed to make the doubled guitar parts indistinguishable.

Close mixing on drums was gaining popularity as it gave a tight sound that the engineer could control. However, the band wanted a big drum sound so insisted on recording the drums using just a few mics in a large room. This gave the drums a monumental and almost splashy sound, while also gluing the different elements of the kit together.

The bass part was recorded in three different ways; one is direct from the guitar (DI), one is direct from the amp (built by John Deacon himself), and one is a room mic to capture some natural ambiance. Queen producer Roy Baker often captured these three takes and blended them to get the most of the bass. He would play around with the phase switches to see which settings best suited the balance and gave the fullest sound.

IS THIS THE RE - AL LIFE

Guitar Melodies

The lead guitar melodies were not improvised or merely a copy of the vocal line, but more of an extension and elaboration of the main vocal melody. May thoughtfully constructed a counterpart melody that builds on the existing material in the song. This is his preferred method of melody writing and says that "the fingers tend to be predictable unless being led by the brain."

This is an excellent approach to melody writing for any music production. When writing a lead line, expand on what melodies are already present in the song to add continuity while evolving the musical ideas.

Technical Details

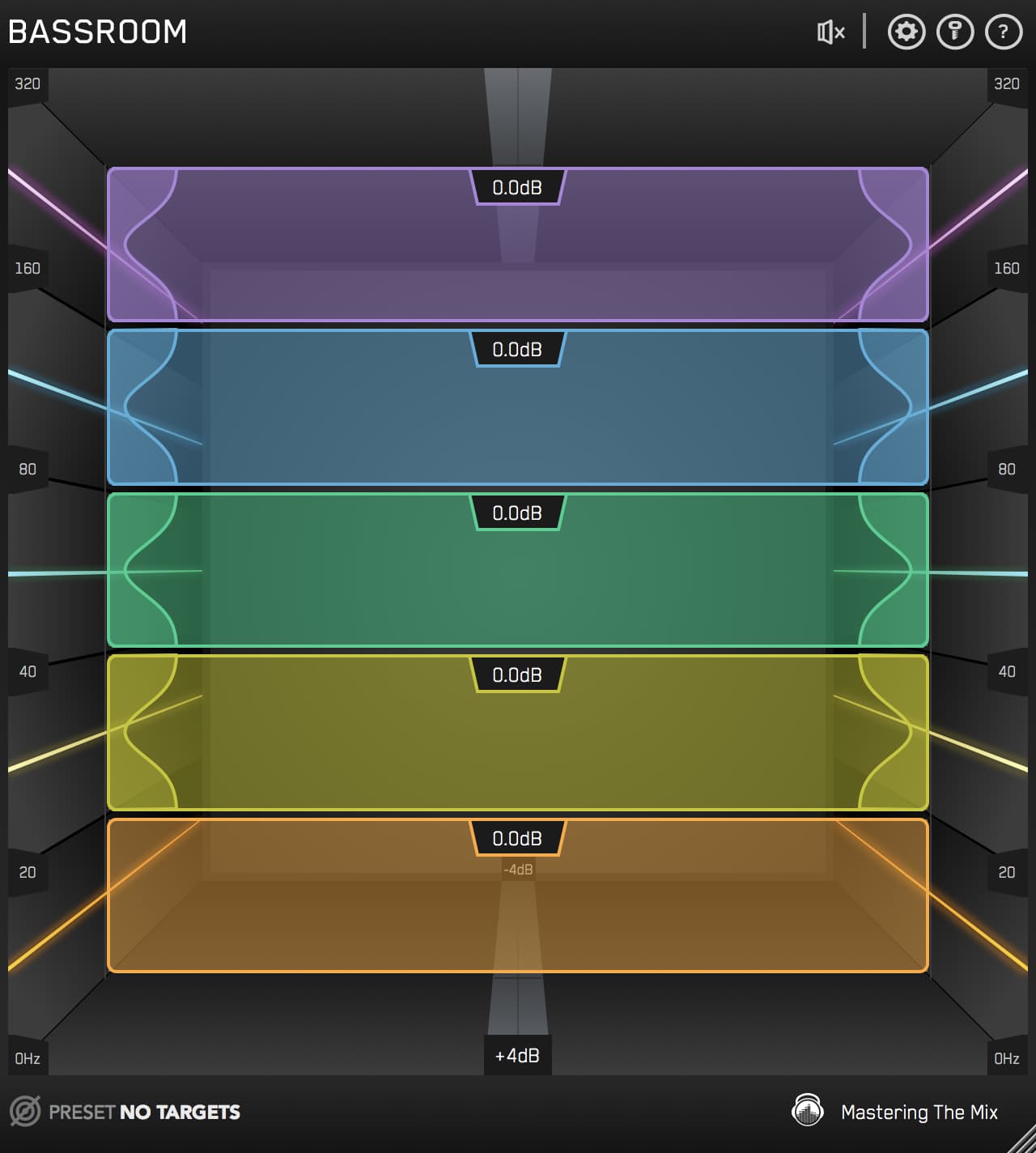

Below, EXPOSE is showing us the at no point does the song get louder than -10LUFS short-term, which is a very moderate loudness achieved with minor compression and limiting. The loudness range is 16.2LU signifying a considerable dynamic range between the sections. This means that when the rock part enters, it feels loud and explosive compared to the much quieter sections of the song. The song also avoids true peak clipping hitting a maximum of -0.14dBTP meaning it won’t digitally distort when played back through analog speakers. The theatrical panning leads to the track having moments of imbalance between the left and right speakers, as shown in red on the waveform. This is only momentary and enhances the drama of recording.

What Did We Learn?

- Teasing your audience by releasing a section of your track can generate buzz.

- Making the transitions flow musically from one section to another helps the sequence and continuity of the song.

- Ambiguous lyrics can lead to a song resonating with the listener in their unique way.

- When stacking harmonies, the timing of each vocal delivery has to be exact regarding rhythm, pitch, and vocal inflexion to maintain intelligibility.

- Changing the tone of instruments throughout a song creates new textures of sound, but also helps the overlap the parts during overdubbing.

- When the kick and bass are placed centrally in a mix, it leaves space in the side channels for other instruments to add low-mid range warmth to the mix.

- A section can feel loud without being over-compressed through the contrast of quieter sections of the song.

Want To See More Songs Decoded?

This blog post is one of 40 chapters in ‘How Pros Make Hits’, an eBook created by Mastering The Mix. Music surrounds us. It’s everywhere. Your music has the potential to connect with millions of people. Don’t produce another second of music without first learning how these pros did it to give yourself the best chance of success.

Visit the How Pros Make Hits webpage to download 5 free chapters now.