From parametric equalizers to multiband compressors, mixing engineers use more tools per project than most carpenters. With so many options to choose from, it can be difficult to know which tool is right for the job. In this blog, we’ll break down the different types of EQs, compressors and reverbs—and when to use them in a mix.

Fixed Frequency EQ

Fixed or selectable frequency EQs are one of the original equalizer designs and were commonly found in analog consoles from the 50s and 60s. Thankfully, you don’t need to own a vintage console to use one—many of these designs have been emulated by plug-ins.

Fixed frequency EQs feature three or more bands, each with several preset frequency options. Some, like the high-shelf on the Neve 1073, are fixed at one specific frequency and cannot be changed.

Fixed frequency EQs do not offer Q controls—only frequency selection and gain. Because of this, they’re better for colorful additive EQ as opposed to surgical cuts.

However, some models, like the API 550 series feature proportional-Q designs, which increase the Q value of a band as the gain is increased. This allows you to pinpoint specific frequencies when making aggressive cuts or boosts.

Semi-Parametric EQ

Semi-parametric EQs are found on modern analog consoles, such as the SSL 4000 E-Series.

Semi-parametric EQ designs typically feature four or more bands, while some also include high and low-pass filters. The midrange bands are fully variable with Q controls, making them ideal for gentle boosts or surgical cuts.

Typically, the high and low-bands are shelf shapes—although more advanced designs allow you to toggle to between shelf and bell shapes. Depending on the design, the frequency for the high and low bands may be fixed, selectable or fully variable.

Parametric EQ

Parametric EQs are the standard digital EQs you find in the stock plug-ins folder of your DAW. Most offer seven or more bands, which can be used to create filters, shelves, bells, and hyper-specific EQ curves.

Each band features fully variable controls for frequency, gain, and Q, making parametric EQs one of the most versatile options.

However, unlike the analog-modeled designs listed above, digital parametric EQs tend to sound very transparent, making them better for subtractive EQ or subtle boosts.

Graphic EQ

Graphic EQs are one of the most basic forms of equalization. Originally utilized by live sound engineers to pin-point and eliminate feedback, graphic EQs come in three different sizes.

31-band graphic EQs are typically reserved for live sound rigs. The smaller 15-band models are used for mobile sound rigs and occasionally found in the studio. There are also modular 8 and 10-band models, such as the API 560, which are commonly found in 500-series racks.

Graphic EQs feature so many bands because they have no frequency select or Q controls. Instead, you shape your own EQ curves by adjusting each band to create shelves, bells or filters.

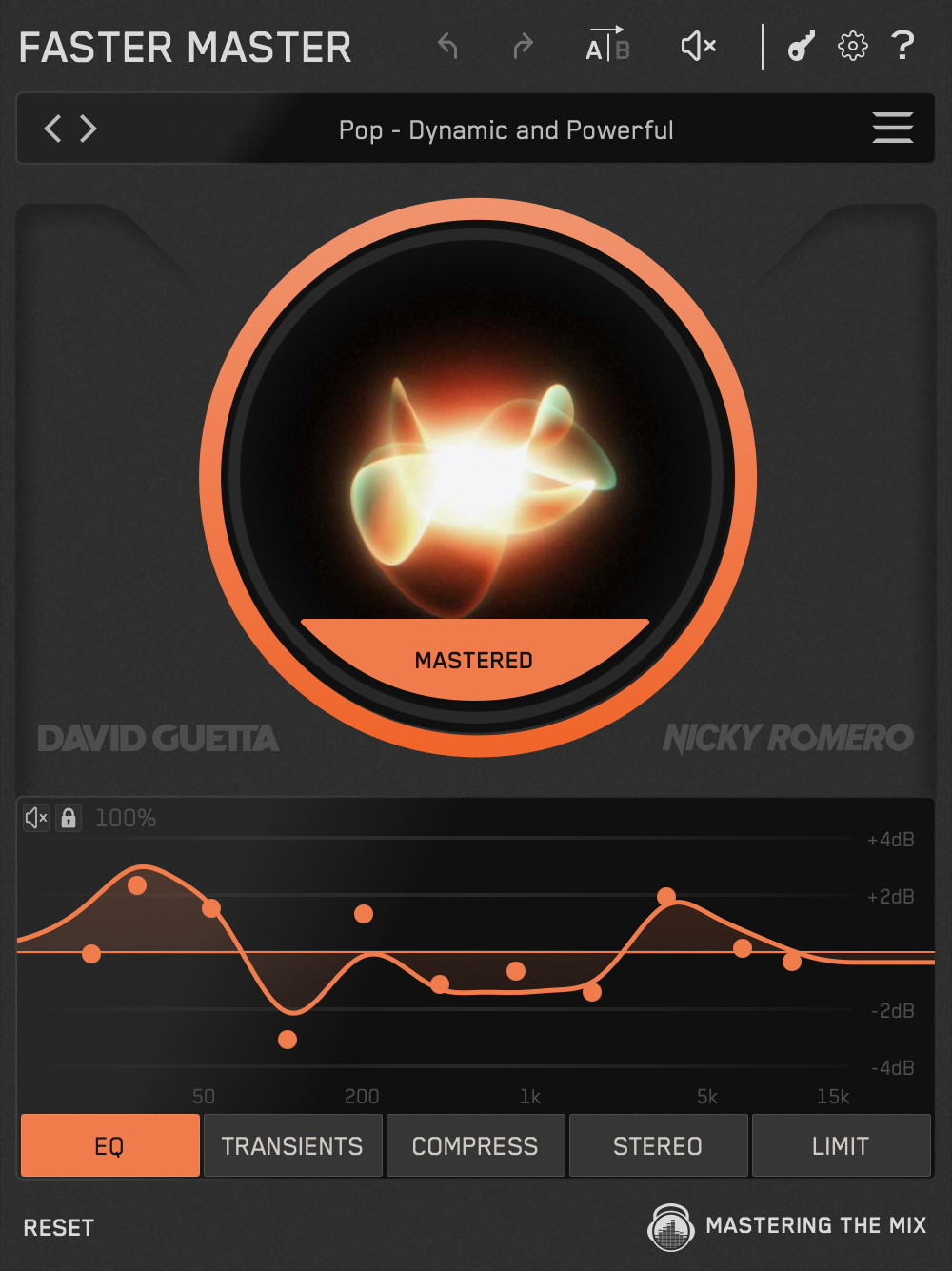

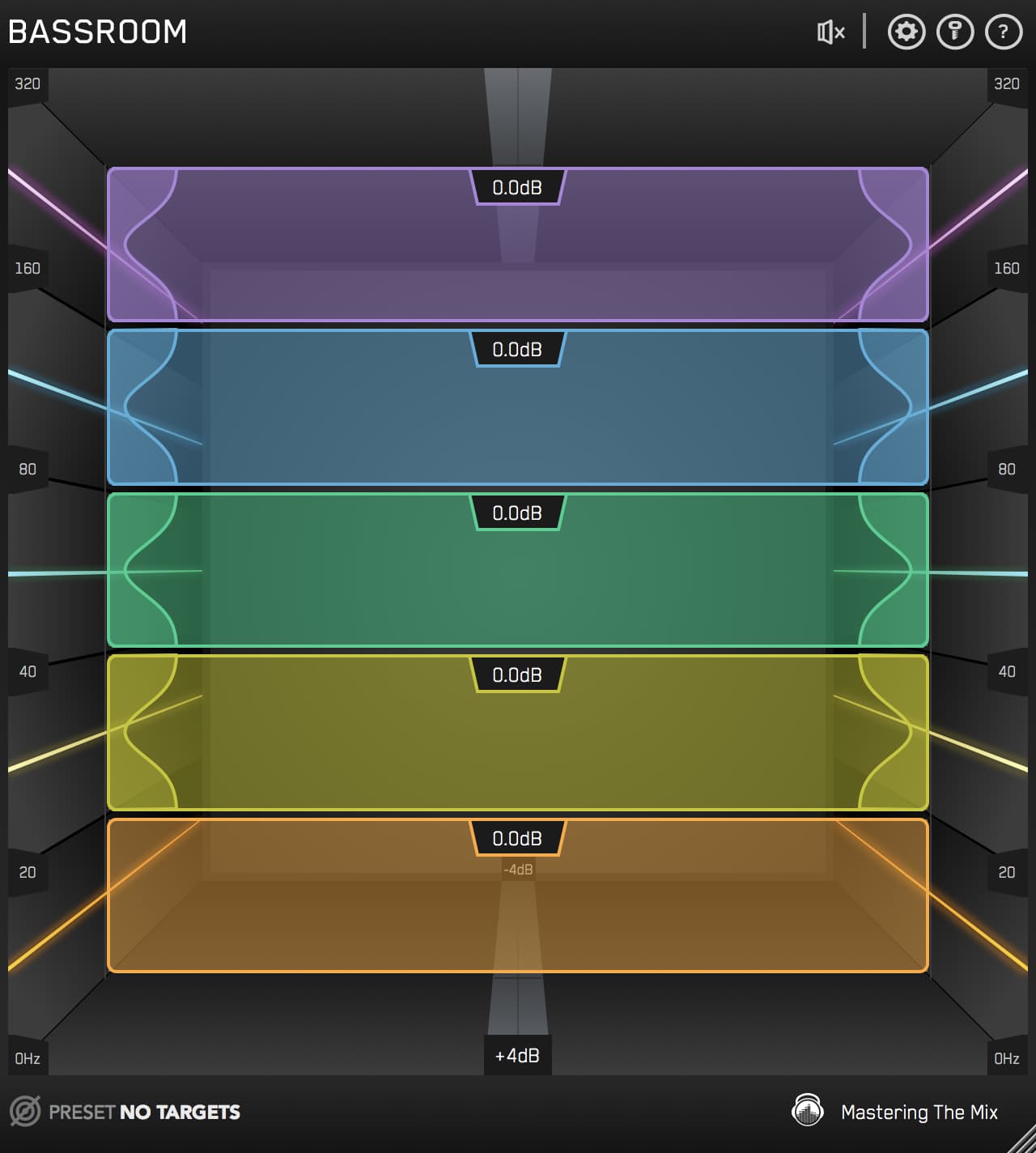

Our very own BASSROOM uses a modified graphic EQ design to pinpoint problem areas in the low-end.

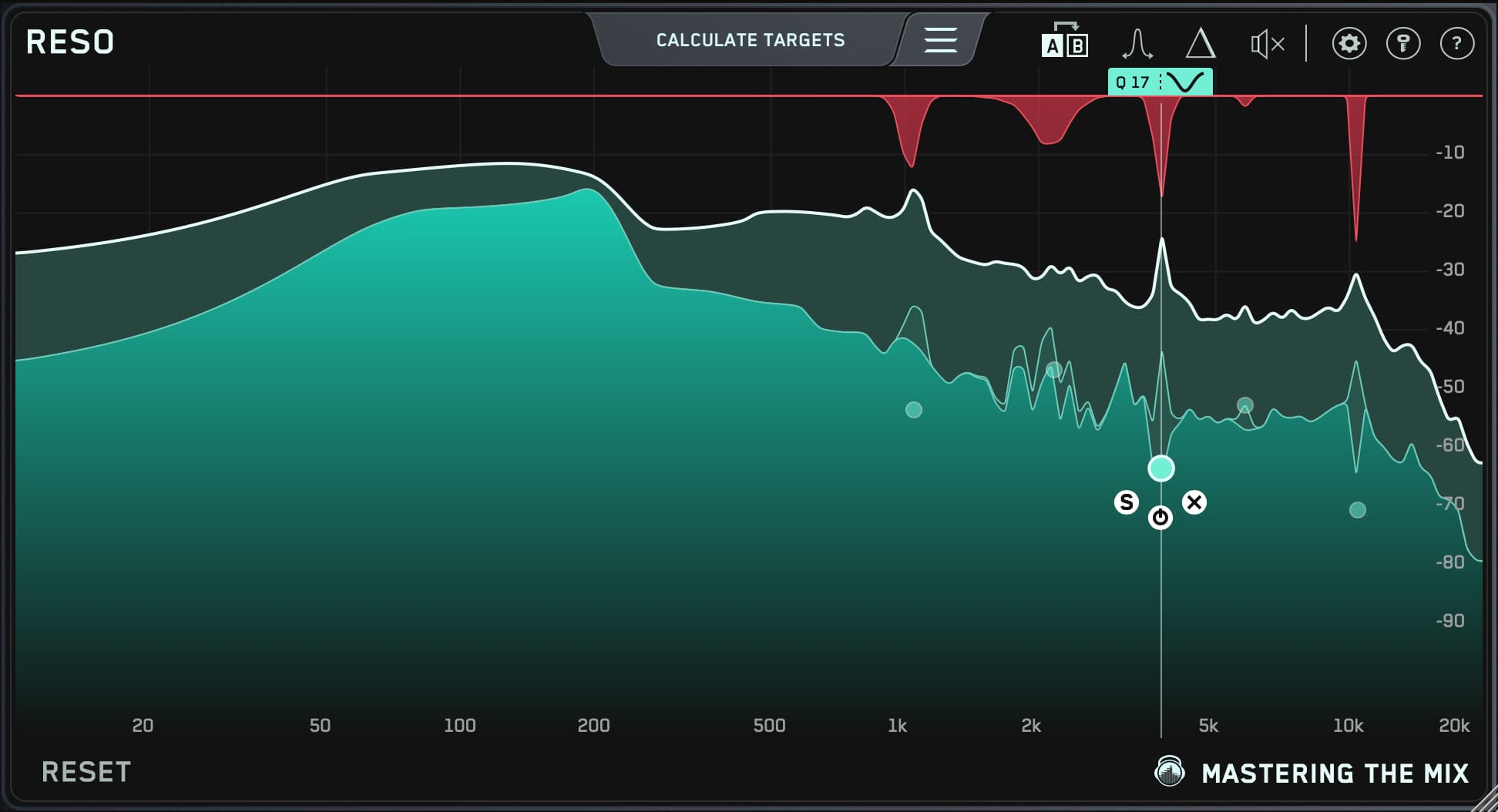

Dynamic EQ + Multiband Compression

Dynamic EQs and multiband compressors are very similar. Both are digital tools with multiple bands that use a threshold to dynamically boost or cut frequencies.

The difference is, multiband compressors use crossover filters, which affect a wide range of frequencies. Whereas dynamic EQs allow you to zero-in on specific frequencies. Dynamic EQs also use upward expansion, which can sound more musical when boosting.

Both tools are great for maintaining a balanced frequency spectrum throughout a song. When a frequency range exceeds or falls below the threshold, that range is attenuated or boosted. This gives you total control.

Optical Compressors

Some of the earliest compressors used optical designs. Often powered by vacuum tubes, optical compressors have a warm, musical sound. One of the most popular examples is the LA-2A.

They have slow attack and release times due to the optical sensor used to trigger compression. As the level increases, an LED gets brighter, signaling the optical compressor to trigger the compressor.

Because of their slow response time and colorful sound, optical compressors are great for squeezing tracks with smooth, steady compression—especially vocals!

Vari-Mu Compressors

Variable-Mu, or Vari-Mu designs are another type of compressor that has been around for over 50 years. These massive tube-driven designs are great for adding vintage vibe to any track.

Known for their variable or program-dependent ratios, vari-mu compressors use a soft-knee style of compression to apply generous amounts of compression without creating artifacts or unwanted distortion.

This makes them great for fattening up tracks with slow and subtle compression, or slamming them to crank up the energy.

Perhaps the most famous vari-mu design is the $30,000 Fairchild 670. Or, you know, you could always pick up a plug-in…

FET compressors

FET compressors were originally designed as solid-state replacements for tube compressors because engineers were getting tired of servicing them.

They’re known for their super-fast attack and release times, which make them great for peak limiting and taming unruly transients. However, they also generate lots of harmonics when driven, making them a prime choice for vocals and other instruments that need to cut through the mix.

Easily, the most well-known FET compressor is the 1176, with its infamous “all buttons in mode." For this reason alone, FET compressors are the tool of choice for aggressive or parallel compression.

VCA compressors

VCA compressors are both the most modern and most versatile compressor designs. They sound the most transparent and offer a wide range of attack and release times. They excel at both peak limiting and leveling applications, making them a versatile, Swiss-army compressor.

There are no real downsides to using a VCA compressor, other than they lack the color and character of the tube-driven and FET designs listed above.

Most modern compressors use VCA designs, but one of the most well-known is the SSL console compressor—a go-to for mix bus compression.

Room Reverb

Room reverbs are the most natural-sounding, because they’re designed to sound like actual rooms.

The size and materials the room are made of can be changed to recreate the sound of almost any room—from a recording studio to your basement. For this reason, room reverbs are one of the most versatile options available.

Room reverbs tend to have shorter reverb times, which make them better for up-tempo songs. They can be great when used in small doses to glue tracks together and make them sound like they were recorded in the same space.

Hall Reverb

Hall reverbs are designed to emulate the sound of concert halls and other large buildings. They typically have very high ceilings, which gives them a unique sense of depth and longer decay times that room reverbs.

Hall reverbs have slightly longer reverb times, and are great for pushing tracks back in the mix. Many engineers prefer them for drums and vocals.

Plate

Plate reverbs were the first “mobile” analog reverb design. They’re made of two metal plates suspended in a giant wooden box. When a signal is sent to the plates, they begin to reverberate, which is captured by a small microphone inside the box.

Dampeners can be adjusted to control the reverb time. Some models even feature plates of different materials to provide a range of tones, making them a very versatile option.

Understandably, plate reverbs tend to have a dark, metallic sound to them, which works great on vocals and snare drums. Don’t be afraid to use a high-pass filter to clean up the low-end!

Chamber

One of the original forms of reverb were actual reverberant chambers. These rooms were made of highly reflective surfaces and featured odd angles for long reverb times.

Chamber reverbs offer tons of color and texture, which can be great for filling out sparse mixes but can quickly get in the way of busy sessions. If you’re going for a vintage vibe, chambers are definitely the way to go.

With the right tools at your disposal, there’s nothing you can’t create! Use this post as a reference next time you’re having trouble getting a track to sound the way you want.